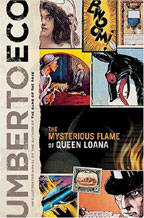

The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana

By Umberto EcoTranslated by Geoffrey Brock

Harcourt $27

Reviewed by Richard Di Dio

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette - Sunday, July 31, 2005

Well, tickle my pylorus with a mysterious flame -- Umberto Eco is at it again.

In his warm, challenging, dizzying and ultimately rewarding new novel, Eco violates Aldous Huxley's maxim that "every man's memory is his private literature." Instead, this latest novel from the scholar and best-selling author demonstrates the power of literature to constitute memory and, with it, the soul.

Yambo, a 60-year-old Milan book dealer, awakens from a stroke with a strange amnesia. He cannot remember his family, yet he can remember everything he has ever read, thousands of books. This remembering is not willful, however. Yambo thinks in passages from books -- his "paper memory" -- which leads to immobilizing bouts of literary streams-of-consciousness. In one Proustian moment, the smell of his grandchildren evokes that "the marchioness went out at five o'clock in the middle of the journey of our life, Abraham begat Isaac and Isaac begat Jacob and Jacob begat the Man of La Mancha, and that was when I saw the pendulum betwixt a smile and a tear, on the branch of Lake Como where late the sweet birds sang, the snows of yesteryear softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves."

(Note: An Internet project is providing citations for the thousands of the novel's literary references.)

Yambo's memories now come only from his reading. He lacks episodic memory, and he cannot explain how his experiences define him. The route to recovery must come through recapturing the episodes of reading.

Sequestered at his summerhouse, Yambo pores through comics, serial novels and old schoolbooks, rereading the literature of his youth. He soon faces unsettling, and perhaps unwanted, memories.

Many of the comics are products of wartime Italy. (Queen Loana is an Italian comic heroine.) Was he an ardent Fascist youth, or did he enjoy the comics because of the adventures? As Yambo reads more and more, he becomes less sure of who he was and is.

This depiction of childhood in a totalitarian state is a unique one, and is helped by many color photos of Italian comic books and movie posters from that era.

However, there is an obvious danger in writing a book in which the only action is the protagonist reading other books. The brilliant writing -- with much credit to Eco's new translator Geoffrey Brock -- and wonderful illustrations don't completely eliminate the tedium of so many unfamiliar references.

Giving up is not an option, however. Fans of "The Name of The Rose" and "Foucault's Pendulum" know that Eco's storytelling is often accompanied by dense sections of unreadable passages (the all-Latin sections in "Rose") and arcane lore (the history of the Knights Templar in "Foucault" which "The DaVinci Code's" Dan Brown must have read).

So get through the Fascist comic books and you will be rewarded with a "mysterious flame." That's the feeling that Yambo gets when a specific book touches his pylorus, the small opening between the stomach and the small intestine.

These flames signal that Yambo is onto something deeper -- a real episode of his life. Ultimately, the most mysterious flame is Yambo's first love, and it soon becomes clear that he needs to remember her face in order to recover himself.

These real episodes are told with all of the skill that Eco possesses, rich characters in emotionally charged scenes full of mystery and heartache.

Queen Loana posits a deep connection between memory and the world. As Eco writes, "the "act of remembering [is] always linked with the creation of a new reality." The act of reading Eco entices us to relive our own childhood memories via the books of our youth. Like Yambo, we reconstitute our lives, becoming someone new through the act of reading and remembering.

Richard Di Dio teaches mathematics and physics at La Salle University.

Note: see original review in Pittsburgh Post-Gazette for a companion interview with Eco written by Bob Hoover, book editor of the Post-Gazette.