A quirky, provocative catalog of 'sublime' creators

Wednesday, November 8, 2006

Wednesday, November 8, 2006

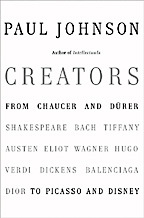

Creators

From Chaucer and Dürer to Picasso and Disney By Paul Johnson

Harper Collins 286 pp. $25

Reviewed by Richard Di Dio

Philadelphia Inquirer - Wednesday, Nov. 8, 2006

Complete the following analogy: Ronald Reagan is to Mark Twain as Bill Clinton is to ... Jane Austen? A trick question on a college entrance exam? No, just one of the odd couplings presented by British historian, journalist, poet, novelist and artist Paul Johnson in his latest analysis of the main movers of history and culture.

Replete with arcane facts, personal reminiscences and trenchant observations, Johnson's Creators: From Chaucer and Dürer to Picasso and Disney is a highly informative, provocative, and maddening look at some of the most creative figures in history. It is also a logical companion piece to his 1998 best-seller Intellectuals. Along with a planned third volume to be titled Heroes, Johnson's long-term project of illuminating the path of modern civilization through individual achievement is well under way.

Johnson's creators are those whose art, architecture, literature, poetry, music and fashion are not just canonical, but "sublime." Their works are their own aesthetic; schools of thought, design and practice can be traced to them. Johnson's taxonomy of creative genius runs from the mid-14th through the late 20th century, and includes not only the obvious heavyweights - Chaucer, Shakespeare, Bach, et al. - but also many others who are not the household names they once were, or should be: Albrecht Dürer, J.M.W. Turner, and A.W.N. Pugin. With his exhaustive command of history, literature, art and culture, Johnson may be unique in also seeing the contributions of Louis Comfort Tiffany and Christian Dior as truly seminal.

Knowing that creativity cannot be defined, Johnson sets as his goal to display its hallmarks. A common component is quantity, and, as if reading a yearbook for a team now in its 600th year, we learn that Chaucer had a vocabulary of 8,000 words, Turner produced 20,000 drawings and watercolors, and Victor Hugo published 10 million words.

Eccentricity, in all of its varied manifestations, is also common, perhaps none more so than superstitions and pre-creation rituals: "Proust needed silence, Dickens mirrors, Byron worked at night, Disney washed his hands." For some, clothing was an outward manifestation of their muse - yet T.S. Eliot was the "last poet to wear spats." And Tiffany, the master of colored glass, "loathed the fauves."

Johnson is at his best when identifying the resonating influence of his creators' works, especially when their writing has clearly influenced his. In describing Twain, he writes that "the whole of [his] vast, sprawling, dog-eared, careless, infuriating, delightful, and inspired output forms a great mountain of detritus which straddles the high road of American writing and forces those involved in it to pick their way over or through it."

The list of Creators is ripe ground for who's on and who's off arguments. No Mozart, scientists, or non-Western writers? One reason for these omissions is structural: Johnson chooses his "top" creator from each time period, and Turner is in Mozart's time slot. The lack of scientists and Eastern writers and artists is harder to accept, and Johnson admits that he has no good answer for not featuring them other than that he has written in his area of expertise. But these arguments are really symptoms of what makes Creators such an accomplishment: Johnson is a formidable and opinionated proponent for his choices. None other need apply.

Some readers may find Johnson's personal recollections unseemly name dropping. Yet these intrusions are more than balanced by observational gems that can only come from a mid-20th-century student-observer. Regarding the publication of Eliot's Four Quartets, Johnson recounts "a puzzled and inconclusive discussion... in which C.S. Lewis played the exegete on 'Little Gidding,' with a mumbled descant from Professor Tolkien and expostulations from Hugo Dyson, a third don from the English faculty, who repeated at intervals, 'it means anything or nothing, probably the latter.' "

Reading Creators gives one an appreciation for the indefinable creativity of those whose works form the cornerstones of our art, culture, and history.

Richard Di Dio teaches physics and mathematics at La Salle University.

http://www.philly.com

Reader Comments